The pandemic has charred modern life. Things we valued—travel, mobility, predictability—have been replaced by the morbid uncertainty of a deepening global health and economic crisis. It was anticipated that the coronavirus would plunge economies into a deep recession. Policymakers had predicted that a worldwide halt in production and disruptions to global supply chains would push millions into unemployment, aggravate poverty and deepen food-insecurity. Government relief measures like guaranteed job security, deferred loan payments, and cash disbursement were expected to help people tide over the worst of the pandemic. Yet, millions continue to languish in compounding uncertainties of daily living.

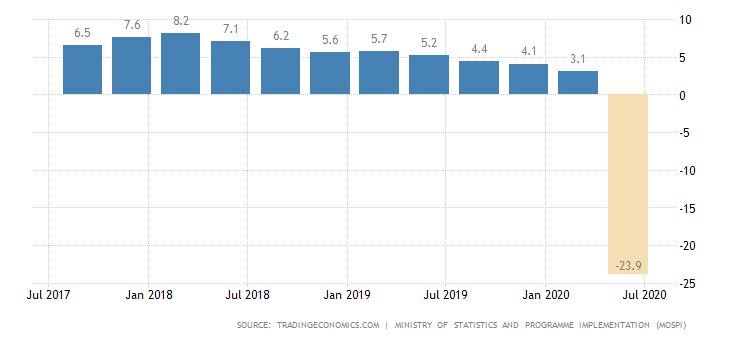

In August, the government released GDP figures for the first quarter of the financial year, which were received with shock and criticism. A contraction of nearly 24 per cent in the GDP indicates colossal damage to the national economy and paints a bleak picture of the future—one where most people (and accountable governments) are desperate to see some signs of hope. Figures for economic activity between April and June (the first quarter) do not reflect increasing employment rates or the increased activity of July and August. But the rising number of new cases in the last two weeks will, predictably, off-set the temporary gains of the last two months.

Some have defended the prime minister and the government’s economic response. After all, Covid-19 is an “Act of God” that has caused the economic contraction. God may or may not have had a role in the pandemic, but India’s deepening economic woes are certainly not a result of the pandemic alone. Covid-19 merely exacerbated structural shortcomings in the economy, which had been ailing long before the coronavirus reached India’s shores.

The Lockdown

The Modi government came to power in 2014, riding on a recent uptick in GDP growth rate that had been increasing consistently since 2011. It was 7.41 per cent when the BJP, on the promise of vikas (development), assumed office. In 2016, the GDP growth rate was 8.26 per cent, a little more than one per cent over the rate of 2014. It has since been falling consistently. In 2019, it was a mere 5.02 per cent. And then came the pandemic.

When the lockdown was announced in late March, there were fewer than a thousand confirmed cases in the country. Most of these were restricted to the bigger cities like Delhi & NCR, Mumbai, Hyderabad and Pune. The 21-day lockdown was brutal. Ad-hoc measures at the centre, lack of preparedness, and the onus on people to ensure their safety made sure that most Indians continued to play catch-up with lockdown regulations. If there was a roadmap for what came after, it was shared with none. Deprived of food and certain of financial troubles, daily-wage labour demanded to return home to India’s hinterland. With no available transport, thousands began to walk home, possibly carrying the virus with themselves.

An increased population in villages added to the burden on the rural economy, which was already in distress because of falling consumer demand over the last few years. Even though the agricultural sector showed a slight growth in the recent GDP figures, the sector is not secure from economic troubles. April—the month during which the lockdown was the harshest—is also the harvest month. Owing to travel restrictions and a loss in demand from closed-down restaurants and hotels, farmers were not able to sell their produce. Bountiful rains have, at this point, saved the sector from an imminent crash, but the village economy still faces a double threat—rising coronavirus infections and severe shortage of cash.

Even as migrant labour return to cities to either resume their old roles or to take on new ones, chances of a speedy recovery remain unlikely, and rising daily cases now pose the most significant threat to the Indian economy. The hope of bouncing back to pre-Covid levels by mid-2021 is bleaker than the hope of finding a vaccine by this winter.

Corporate Tax-Cut

The effects of Covid-19 and the lockdown on a struggling economy are apparent. They are, however, only the immediate causes for economic distress that has been building up over years of poor economic policy and decision-making at the macro-level.

Last year, there was widespread concern about the falling growth rate and slowing consumer spending. Malls were empty and nearly every store was willing to offer large discounts in order to increase sales. Indians had apparently not been spending long before Covid-19 made it impossible to do so. Unemployment, too, had touched a 45-year high. To boost economic activity, the government announced a mid-year policy reform: corporate tax cut, through which the tax rate of large companies was brought down from 30 per cent to 22 per cent. The underlying assumption was that this would prompt benefitting companies to invest in newer projects, which would in turn generate employment and boost manufacturing. The tax cut cost the government Rs. 1.45 lakh crores but failed to achieve its objective. In retrospect, that money could perhaps have been deployed towards the stimulus package that the Finance Minister announced mid-May, and which, at nearly ten per cent of the GDP, fell seriously short of expectations.

Policy Failures

This slowing growth, of course, rides on other longer-term factors: rash policies implemented by the Modi government in its first term. Much has been said about the fateful evening of 8 November 2016 when the prime minister, in his signature style, announced the Demonetisation. With a four-hour notice, over ninety per cent of India’s currency in circulation was declared null and void. The black money that demonetisation was supposed to have washed out was back in the economy within months, but the powerless 500 and 1000 rupee banknotes left a trail of economic hardship, panic, confusion, and misery in their wake. Millions of Indians, who understood nothing of our banking system and remained outside of it, lost their life savings. Mr Modi learnt nothing from the episode, but retained his flair for four-hour notices.

The Goods and Services Tax or the GST was, in a historic first, passed by a midnight session of the parliament in July 2017. Three years later, its benefits remain questionable. The GST was, in principle, a much-required policy change. It would significantly simplify the tax regime, remove the duplicity of taxation, and erase the uncertainty of tax rates in different states. In that respect, it was welcome. But the government added a body of unfulfillable promises to the GST regime.

Indian states rely heavily on revenue earned from taxing the sale of goods and services to fund the expenditures of the state government. Before the GST, they collected this tax directly through various taxes. Since they would lose revenue by implementing the GST, the centre promised ‘GST compensation’ for a period of five years. Now, the centre cannot uphold this promise. Moreover, under the GST regime, certain ‘luxurious’ items are taxed heavily, deterring people from spending money, and further stalling the economy. So, to keep up its promise of payments to state governments, the centre taxed people heavily, taking even more money away from them just six months after demonetisation.

An Uncertain Road Ahead

India’s weak financial system has been at the forefront of many discussions, especially in light of recent cumulative distresses. Even so, no one had foreseen a contraction of 24 per cent in the GDP. This number signifies institutional malaise aggravated by a botched response to Covid-19. The government could be commended for its swift actions against the virus. But that would beg the question of the labour migration crisis, the farmer suicides and the job losses. Most importantly, it would question the empty road ahead, devoid of any planning or clarity. While it remains to be seen what 2021 will bring to the Indian economy, it cannot be denied that a hasty lockdown, lack of preparedness, outright denial of community transmission and, reverse labour migration have not only damaged our society and its confidence, but have also brought our economy on the brink of a serious crisis. So much for Aatmanirbhar Bharat.

Aarushi Aggarwal is Associate Editor at ALMA MAG. On most days, she studies foreign investments and writes about India’s economy. She has recently forayed into essay writing.