Image: Farren van Wyk’s collection of eight photographs titled, “Thirppy.”

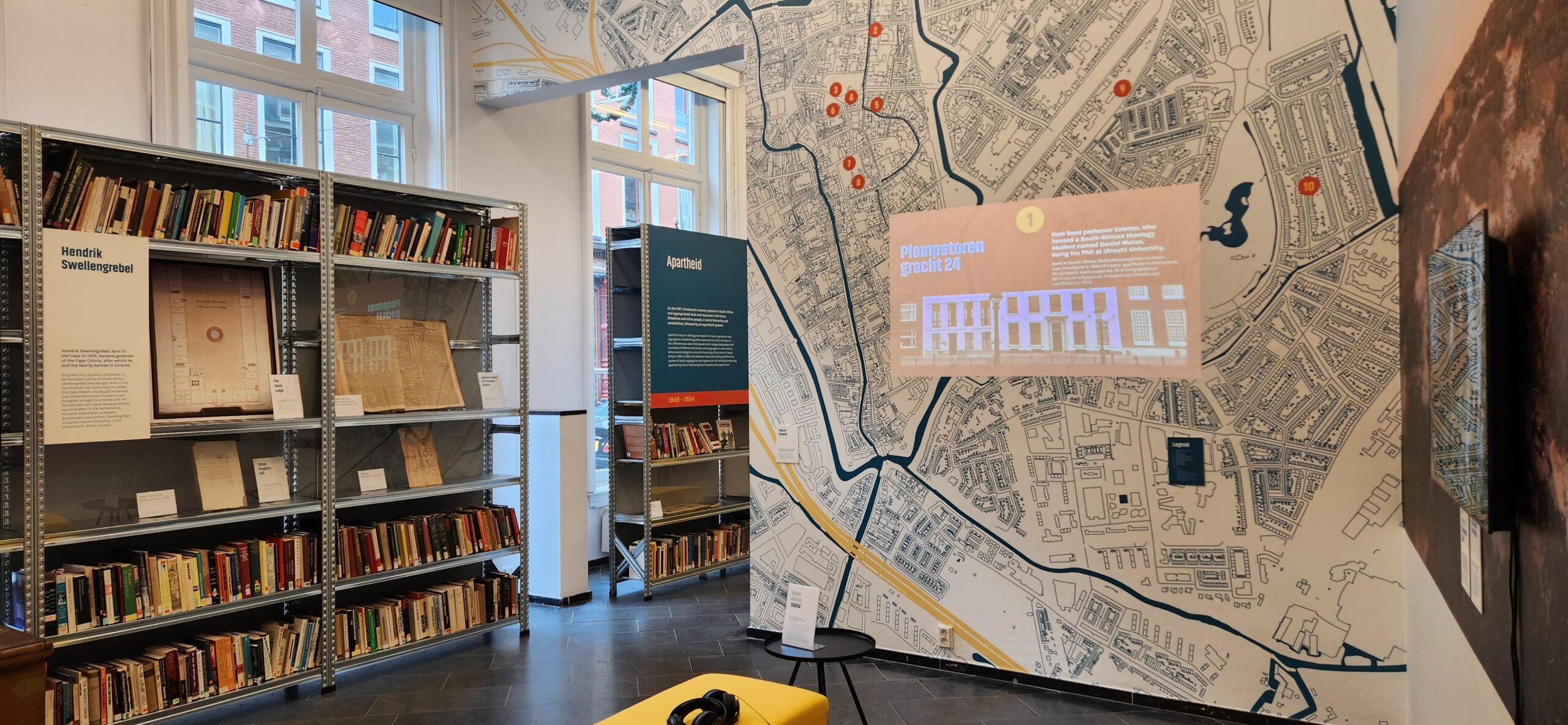

The subtitled words face the pavement in front of Utrecht University of Arts’ (HKU) space for new art and media located at Minrebroederstraat 16. They serve as a primer to the narratives and conversations in focus at the space’s latest exhibition, CAPE X UTRECHT: Hidden histories of slavery and its afterlives. The exhibition reviews and contextualizes the history of Dutch imperialism in South Africa through a multimedia approach. The small but immensely powerful space was curated and designed by HKU fellow and cultural historian Nancy Jouwe in collaboration with The Black Archives. In 2011, Jouwe developed a walking tour of Utrecht called “Traces of Slavery Utrecht” and published a book titled “Slavery and the City of Utrecht” in 2021.

Sitting on a reflection bench in the second room of the exhibition, Jouwe recounts protesting apartheid outside the South African embassy in Amsterdam on a sunny afternoon in the mid-eighties. In what she describes as a time when she was heavily involved in the squatter and activism scene, Jouwe was already aware of the stories and struggles of apartheid.

“I was at Utrecht University when I was fortunate to have bell hooks as a lecturer, as she was a visiting professor for three months,” Jouwe says. In one of the classes she said, ‘Apartheid is the most famous Dutch word.’ However, when I repeated it to Dutch people, even those I worked with on the history of slavery, they would get upset, telling me, ‘no, it’s Afrikaans, not Dutch.’ This reflects Dutch ignorance about this history and on the other hand, their reluctance to be associated with it because they do know—which is a paradox.

A multimedia approach to History

Jouwe and The Black Archives’ experience and expertise have enabled them to create a detailed and multi-layered intervention to address this paradox. Visitors are first greeted by a quick lesson on the etymology of apartheid just outside the exhibition space. Upon entering, they find themselves in a room flanked by bookshelves on one side and a panoramic photo of the South African coast by Carine Zaayman on the opposite wall. Zaayman also provided advice for the exhibition and contributed to some of the literature found in the space. Starting with photos and text, the exhibition gradually incorporates preserved newspaper clippings, old chests intended to carry stolen valuables from the colonies, video projections, poetry recitations, and documentaries. Jouwe mentions that this multimedia approach, along with everything being presented in English, is designed to enhance accessibility.

“The oldest artist in this exhibit is 70, the youngest 30 — so there’s three generations here, and they all find it important to work transnationally,” Jouwe says. “And if you work transnationally, you almost automatically will work multimedia because you have text, you have video, you have audio, you have photos, because you want to share your work in different ways.”

Just beyond the main entrance to the room is an introduction to the history of Dutch imperialism and involvement in slavery, accompanied by two guiding questions. The questions, designed to be a framing device for the conversations in the room, interrogate how people in contemporary South Africa may still be impacted by Dutch imperialism, and who remembers the history of slavery across the Indian Ocean. Notably, the curators have chosen not to provide answers to these questions, fostering a sense of introspection that culminates in the reflection bench where Jouwe sits.

“The most important thing about this [exhibition] is that we want people to understand that this is about them,” Jouwe says. “When you enter this space, this is not about something that’s detached from you: it’s about you. So, we’re trying to invite people to think about how is it about you? And for everyone the answer will be different, so obviously we cannot answer for them.”

As we talk, South African poet Diana Ferrus’ voice filled the reflection room with her filmed reading of “I have come to take you home.” Ferrus wrote this five-stanza masterpiece while enrolled in the Gender Studies program at Utrecht University in 1998. The poem is dedicated to Khoekhoe woman Sarah Baartman, who was born in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa in 1789. Baartman was an enslaved woman, who was displayed in exhibitions around western Europe for several years. After her death in 1815, her remains were placed on display in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris until 1986. The refrain of Ferrus’ poem, “I have come to take you home,” advocated for returning Baartman’s remains to South Africa: a call that was raised by Nelson Mandela in 1994. The exhibition credits the poem’s impact with helping secure Baartman’s return to South Africa in 2002. The pairing of Ferrus’ face and voice with her words serves as a reminder of her aspirations and successes, grounding and resonant in the horror of Baartman’s story.

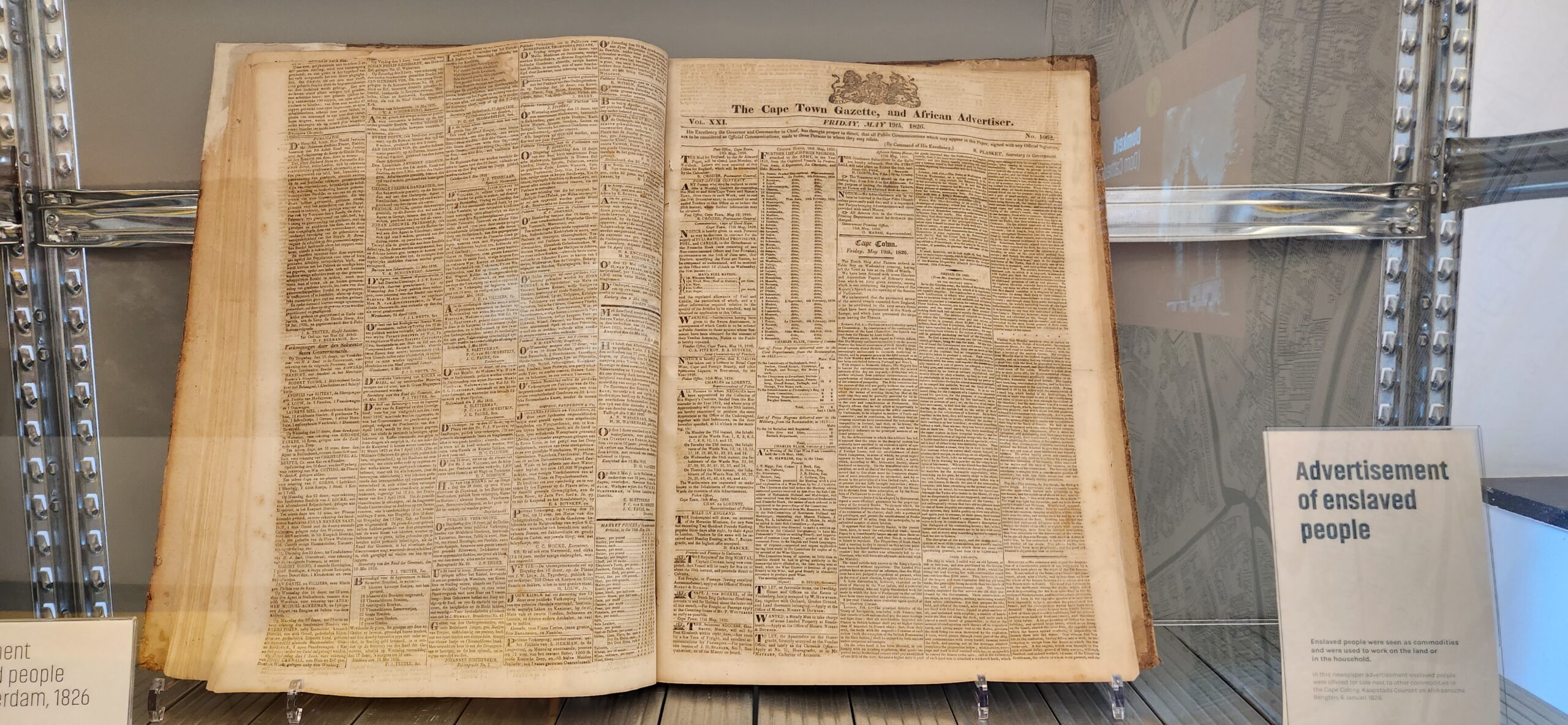

On the wall opposite Ferrus’ poem is a collection of eight photographs showing colored South African women, men, and children who belong to a gang in a segregated and impoverished area of South Africa. The collection, named “Thirppy” after the family represented in the images, was photographed by Farren van Wyk in 2015. In the accompanying plaque van Wyk explains her connection to and motivation in capturing these images.

“Thirppy explores the historical traces of gang culture within Coloured communities to counter its perception of male violence and show the deeper layers of it being a means of survival and brotherhood,” van Wyk writes. “Within the intimate family setting, I became a part of Thirppy’s family and portrayed their day-to-day life while they too portrayed me. They live in the Coloured appointed segregated area and are impoverished as nothing changed after Mandela became president in 1994, the year that apartheid was officially abolished. Being racially classified as Coloured myself and immigrating to The Netherlands at a young age, I have a double gaze in which I use portraiture to decolonize the unjust image of the community I was born into.”

Confronting the living past

Having walked through this complicated and compelling multimedia exhibition on the history of slavery and apartheid, visitors are finally confronted with how the past intersects with the present. On a poster labelled “Healing and reparations,” the curators explain that the current Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte, the mayors of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Utrecht, and The Hague, as well as King Willem-Alexander, have all issued apologies for the Netherlands’ role in the slave trade within the last few years. None of them mentioned South Africa.

The King’s apology was issued on the first of July this year, and though it was unknown to the curators when they first began developing the exhibition, the royal family will embark on an official state visit to South Africa between October 18 and 20. The final day of their visit is scheduled at the Western Cape, historically marked by Dutch colonial oppression. However, the official announcement from the royal house does not explicitly acknowledge Dutch involvement in the enslavement of people in South Africa. Instead, the royal couple plans to “reflect on the two countries’ shared past during a visit to the Iziko Slave Lodge.” This reflects a characteristic tendency in Dutch discussions of race and colonialism to employ euphemisms.

“It’s really important to realize how the Dutch find it difficult to think and talk about race, how deeply that is intertwined with, if at all, they think and talk about colonialism,” Jouwe says. “This is also why colonialism is often represented, for instance, in institutions like the museum up to very recently as something glorious.”

“The Golden Age captures the notion of glorifying that past rather than saying there was violence involved,” Jouwe continues. “There were millions of people being not just disenfranchised but taken prisoner and being forced to work for free under very harsh conditions, being dehumanized.” Jouwe then clarifies that this shift in discourse has been largely driven by grassroots efforts and the persistence of post-colonial communities striving for decades to bring these stories to the forefront.

CAPE X UTRECHT welcomes all to explore its thought-provoking exhibition, which is open to visitors without an admission fee until November 4. In the coming weeks, Nancy Jouwe plans to host panel discussions featuring many of the artists whose work is on display. For additional information, please visit the exhibition’s website.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article do not reflect the political stance or opinions of ALMA and the magazine staff.

Kushagra Kar is a freelance writer and editor. He has edited and contributed news and cultural writing to Recycling Today magazine and its subsidiaries, Recycling International, and The Oberlin Review. He also worked as a production assistant on an HBO documentaries like “Time Bomb Y2K.” Kar has lived in Nigeria, the United Arab Emirates, and India; and hence developed a keen interest in post-colonial discourse.