What Her Friend Said

to the foster-mother (who is guarding her carefully)

Bless you, Mother, listen.

She climbs the round garden rock

that reeks of the meat of

sacrifice,

she looks at the flowering

hilltops of his country,

and she stands there forever

in her sapphire jewels:

only in this way

will her sickness

find its remedy.

– Kapilar

Ainkurunuru

Translated by AK Ramanujan, From Poems of Love and War (1)

How much of the outside world enters our home? And how much of it seeps into our language, our writing, our emotions? It is a fascinating thing to think about, this journey of the public entering the private and travelling back to the public through our words, a process almost economical in its exchange. If human emotions and relationships exist in the private space, then any social interaction we have is pushed towards the public space. The gap that exists between our personal lives and our outer reality, between the private and the public, is brought to life through words that bridge that very gap. And that gap is where poetry thrives.

I was speaking with my friend Neha about the relationship between poetry and space when she made an interesting observation. “It seems to me,” she said, “that poetry does two things: it either contracts its surrounding space or expands on it.” Indeed, poetry has the ability to bring entire worlds into itself succinctly in crisp verse, while it can also focus on a singular object in the space around and encourage one to reread it through the poem. Arun Kolatkar’s Kala Ghoda Poems urge the reader to see Bombay through the scraps of dirt and the street-dwellers who turn a cosmopolitan, bustling city upside down. “Preludes” by T.S. Eliot paints a grim portrait of a dead London, making the reader question the role of the urban flâneur. Wislawa Szymborska’s “The End and the Beginning” is a poem jarring in its simplicity, asking the reader to look closely at even the quaintest, calmest of places, which might have been ridden with war, violence and mass graveyards. Tamil Sangam poetry takes us into its world from 2000 years ago and demonstrates how human experiences of love can remap natural landscapes that were significant to, and a part of, these intimate experiences.

TAMIL SANGAM POETRY

Tamil Sangam literature is believed to have emerged between the 1st century BCE and 2nd century CE. The name ‘Sangam’ is derived from the Tamil word for the meetings and conferences that would take place amongst great scholars, poets and gods in the Pandyan kingdom of Tamil Nadu — then Tamilakam. During each ‘Sangam’, poets would perform and recite poetry.(2) The Sangams apparently lasted for years; the third Sangam is said to have gone on for 3700 years. In the 19th century, the poems were discovered in a debilitated state on scraps and leaves, almost destroyed. Luckily they were revived during the 19th century, and during the 20th century, A.K. Ramanujan and George Hart, among others, took to translating them.

Sangam Poems are of two types: Akam, or love poems, and Puram, or war poems. In other words, poems belonging to the ‘inner landscape’ and ‘outer landscape’ respectively.(3) The Akam poems are incredible for being highly stylized, erotic, secular, formalised forms of poetry. They form, in A.K. Ramanujan’s words, an “inner landscape” that is mapped according to an outer landscape. These love poems are intimate and private, arising from human emotions and relationships situated within an external reality. There are strict conventions on how to evoke love and war, generally determined by different landscapes.

Akam poems are generally narrated from the first person point of view of a woman in love. These poems follow a specific grid of poetic tropes that express the sensual, erotic longingness of the narrator. It becomes interesting to analyse these highly stylised, evocative poems through distilled words on a page read by us, the modern reader. The words in Akam poetry carry the outer landscape into the inner one, acting as a bridge between the poems and the space around them. This is done through the linguistic trope of metonymy, or “Thinnai.”

METONYMY AND SANGAM POETRY

A.K. Ramanujan believed metonymy to be “the master trope of Tamil thought”, and that this was made evident through the Tamil Sangam poems.(4) But what is metonymy? Metonymy, as American-Russian linguist Roman Jakobson spelled out in his essay ‘Two Aspects of Language and Two Types of Aphasic Disturbances’, is a figure of speech that acts on contiguity; a single word may lead to many others and we may derive our meaning through these referents and cultural context in which it is situated. Metonymy works on the basis of combination — “any sign,” Jakobson tells us, “is made up of constituent signs and/or occurs only in combination with other signs.”(5) Which means that any linguistic unit in fact finds its own context in a more complex linguistic unit, binding them into a superior unit of contexture and combination, all connected through contiguity. Essentially, metonymy is focused on the referent of the linguistic unit. Thus, a metonymic word connects us to other words that are all based in the same context, from which we may derive multiple meanings.

Tamil Sangam Akam poems are founded upon a linguistic trope called ‘Thinnai,’ which is essentially metonymy. These are words of the outer landscape which exist in contiguity to the inner landscape:

-

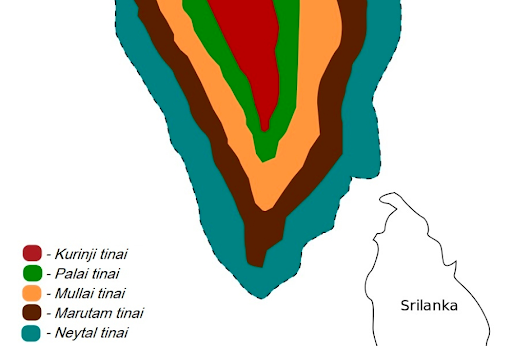

Kurinji: Kurinji is a mountain flower that grows in hilly, mountainous regions. The mention of Kurinji in Akam poems indicates the sexual union of lovers. The people associated with this trope are tribal occupants of hills.

-

Mullai: Mullai is jasmine which grows in forests. This flower, when mentioned in poems, indicates a lover patiently waiting for her love’s return. This forest land is populated by peasants.

-

Marutam: trees which grow red flowers, Marutam are found in pastoral regions. They indicate infidelity of sorts and grow in lands occupied by agricultural farmers.

-

Neithal: Neytal are water flowers that are found at seashores and they indicate the act of impatiently waiting for a lover’s return — just the opposite of Mullai. This region belongs to fisherfolk.

-

Palai: the evergreen tree, or Palai, is found in wastelands and signifies hardships, separation and estrangements between lovers. The people occupying wastelands are travellers and dacoits. (6)

In these cases, a single object from the outer natural landscape — generally a flower — is a referent for a location, which in turn refers to an act/action, further referring to an attached emotion. This contiguous string that is embedded within the Thinnai makes it a metonymy. Furthermore, each Thinnai is indicative of the ecological divisions in various societies based on their labour, and the transition from tribal and nomadic to peasant, fishing and farming populations. As each society evolves so do social hierarchies. Although caste and religion are never explicitly mentioned, there are hints of an established social strata. For instance, in one Neithal poem, Akunanuru 110 by Pontaip Pacalaiyar (translated by George L Hart), a woman tells her lover that “This food is not for you/ it is moist fish, eaten only by low people.”(7) It ends with her waiting impatiently for her lover’s return from sea.

More examples of these metonymic words are seen in the following poems:

What Her Friend Said

to her, before the rains

Is your crop of millet

parching?

Look, the raincloud sits

on the sapphire hills of

your man

like fat on a cut of

meat.

– Kapilar

Ainkurunuru

Translated by AK Ramanujan, From Poems of Love and War (8)

This sensual poem uses the metonymic trope of the hill to denote a lovers’ union. In this case, the woman’s friend pokes fun at her longingness and points to the ‘sapphire hills of [her] man’ — derived from the sapphire Kurinji flowers that adorn the hills. All the woman has to do to satisfy her desire is to unite with her lover, the “man of the hills” as he is popularly called in other poems. Women, in many of these poems, have an established, confident relationship with the outer landscape where they meet their lover, thus indicating the agency they possessed over their body, sexuality and physical movement. The public space is not just for men, and women are not confined solely within the private sphere.

What She Said

When my lover is by my side

I am happy

As a city

In the rupture of a carnival,

and when he is gone

I grieve like a deserted house

in a little hamlet

of the wastelands

where the squirrel plays in the front yard.

– Anrilatu Munrilar

Kur 41

Translated by George L Hart, Poets of the Tamil Anthologies (9)

The wasteland appropriately implies a separation between lovers, as ‘she’ here is talking about her lover who is gone. Estrangement and separation are referents to the wasteland and the people who occupied the landscape — travellers and thieves. Another similar instance is Akananuru 77:

Akananuru 77

“Leaving her lovely face to grow pale

it would be a fine thing

if I were to gather wealth,

adventuring in the difficult wilderness.”

This plan took over my heart

without my knowing its danger.

In the burning heat, thunder-spitting clouds have gone away,

people stop and point out old, barren places

deserted by those who live there,

[…]

red-eared vultures pick up the intestines of men

who gave their lives for victory in battle

and spread them out so no one feels dread[…]

– Palai

Marutan Ilanakanar

Translated by George L Hart, Poets of the Tamil Anthologies (10)

In the above poem, a young man is separated from his lover as he ponders whether or not he should return to the barren wasteland where “her eyes filling with cool tears will strike [him] down”. Travellers and thieves slip in and out of wastelands, and separation from their lovers is inevitable.

What her Girl-Friend Said

The sands are like heaped-up moonlight.

Right next to it stands all by itself,

as if all night were crammed into it

the cool dense shade of a flowering grove

of the black punnai.

Our man has not come back.

Only our brothers’ fishing boats

will return from their hunt

of many kinds of fish.

– Aiyur Mutavan

Kur 123

Translated by George L Hart, Poets of the Tamil Anthologies (11)

Here the poet includes the dark ‘punnai’ tree which blooms white flowers within the natural ‘Neithal’ landscape. The girl’s friend is bemoaning how they are patiently waiting for her lover’s return. For the fisherfolk living in the area, this is custom: men go out to sea in search of fish, and women wait for them to come back. Interestingly, the ‘punnai’ tree grows in coastal areas and its wood is frequently used for shipbuilding purposes. So the natural surroundings are intricately tied to the labour of the region and the experiences of young lovers.

Akunanuru 136

They served white rice full of ghee and meat,

perfectly prepared.

Their generosity unbounded, they honoured their guests.

[…]

The great kettle drum roared with the loud marriage drum;

the girls who had washed her for marriage looked on,

their flowerlike eyes unblinking, and hid themselves;

and her relatives put her on a white thread

and the cool fragrant buds of the tubar akurai,

whose petals spread dark as polished sapphires

in valleys where large calves

graze on the forked, dull leaves of vakai plants

with soft flowers.

And they made her lovely with pure garments.

[…]

Then they came, arousing my desire,

and they gave her to me with beautiful ornaments

[…]

That night, she, her chastity perfect,

as close to me as my body to my life,

covered herself with her still unwrinkled garment.

[…]

I pulled off her garment.

Her form exposed glistened like an unsheathed sword,

and she, unable to hide,

took off the bright garland of lilies that held her braids

and covered herself

with the darkness of her thick black hair

full of flowers humming with bees

and, ashamed, begged and pleaded with me.

– Marutam

Virruru Muteyinanar

Translated by George L Hart, Poets of the Tamil Anthologies (12)

The Marutam metonymy in this poem is made apparent first with the vivid description of agricultural settlements and the introduction of customs and rituals, such as marriage. The ceremony takes place in a valley busy with calves grazing and plants growing, where the community comes together for occasions like this marriage. In Kurinji, Neithal, Mullai and Palai poems, where societies were tribes and fisherfolk or travellers, there was no shame or fear attached to sexual acts since desire and sexual union was bereft of social customs. The enforcement of sexual union only after a marriage ceremony in fact takes away the woman’s sexual agency here; she is ashamed and fearful of the man’s dominance.

THE PRIVATE AND THE PUBLIC IN SANGAM POETRY

I believe that Tamil Sangam Akam poetry interacts with the space around it in two ways: one, its objective reality shapes the inner world of human emotions and language, and two, the inner world in turn shapes the space around.

Akam poetry’s objective reality plays just as much of a role as the lovers do in sexually uniting, waiting patiently or impatiently, committing acts of infidelity or being estranged from one another. The hills provide space for sexual union and the “man from the hills” is often personified to be the hill himself. The coastal seashore takes lovers away while women wait for them patiently there; the wasteland is prickly and barren, like a love that is filled with hardships; and agricultural land alters the act of sex and love entirely, fuelling it with social customs.

Poetic language and poetry’s objective reality makes for a dynamic relationship — both influence each other. A.K. Ramanujan writes that Sangam poems complicate the simple act of verbal communication between sender and receiver that Jakobson deemed was the role of poetic language.(13) Kurinji poems of sexual union are narrated from the perspective of an unnamed woman who is either speaking to her friend, lover, or foster-mother, or speaking while her foster-mother or lover is within earshot. The poems create senders and receivers within themselves, with the added layers of the poets who performed them at Sangams, the writers who wrote them down, the scholars who discovered them a century ago and translated them, and us, the readers, who read them in the present. Whether girlfriends are speaking to each other in a code about meeting their lovers, which their foster mother should not understand, or whether it is spoken for their lovers to know where to find them, we become part of this exchange by accessing the poetry itself. The poems are ridden with irony, indirection, implied meanings, internalised contexts, meta-codes and multiple receivers.(14) The metonymies, or Thinnai, in these poems help us perceive natural spaces and landscapes through social and cultural norms of the time, perhaps even letting us in on certain codes that lovers would speak in when they planned to unite. The unabashedly erotic, secular and male-fetishising female voice helps us gain perspective on certain histories that aren’t present in common majoritarian narratives. Natural spaces of hills and forests and seashores lending themselves to acts of love and longing help us in studying the pertinence of geographical maps and the utilitarian purposes of social spaces.

The relationship between the public and private space in poetry is, evidently, an intimate one. Sangam Akam poems blur the line between the private and the public. Thinnai metonymies and their chain of contiguity help us derive knowledge about people and societies in various landscapes. How people love is very telling of how tolerant a society is and how labour and religious hierarchies structure it. Poetry thus shapes our understanding of public spaces, and as our objective reality keeps changing, so does poetic language. Sangam literature thus carries entire worlds of geography and history through sharp, incisive poems. The poems let us in on cultural codes that connect a historical past with immortal, relatable human emotions of love and loss. Akam poetry exists in that sliver between the private and the public, between the inner and the outer landscape, thereby changing our perspective of both.

-

Ramanujan, Attippat Krishnaswami, and David Dean Shulman. Poems of Love and War: From the Eight Anthologies and the Ten Long Poems of Classical Tamil. Columbia University Press, 2011.

-

Venkatesh, Karthik. “Sangam Era – Of Literature & Life (3rd BCE – 3rd CE).” Live History India, 11 July 2020, https://www.livehistoryindia.com/history-of-india-2000-years/2020/07/11/sangam-literature. Accessed 15 July 2020.

-

Ibid.

-

Bate, Bernard. Tamil Oratory and the Dravidian Aesthetic: Democratic Practice in South India. Oxford University Press, 2011.

-

Jakobson, Roman. “Two Aspects of Language and Two Types of Aphasic Disturbances.” 1956. Fundamentals of Language. By Roman Jakobson and Morris Halle. 2nd ed., Rev. Mouton, 1971, pp. 69-96.

-

Venkatesh, Karthik. “Sangam Era – Of Literature & Life (3rd BCE – 3rd CE).” Live History India, 11 July 2020, https://www.livehistoryindia.com/history-of-india-2000-years/2020/07/11/sangam-literature. Accessed 15 July 2020.

-

Hart, George L. Poets of the Tamil Anthologies. Princeton University Pres, 2016.

-

Ramanujan, Attippat Krishnaswami, and David Dean Shulman. Poems of Love and War: From the Eight Anthologies and the Ten Long Poems of Classical Tamil. Columbia University Press, 2011.

-

Hart, George L. Poets of the Tamil Anthologies. Princeton University Press, 2016.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid.

-

Rodríguez Guillermo. When Mirrors Are Windows: A View of A.K. Ramanujan’s Poetics. Oxford University Press, 2016.

-

Ibid.