On most days, I entertain the idea of checking out that new show making the rounds on Twitter, only to rewatch another comfort episode of Parks and Recreation. Turns out, it’s not just me—old favourites like Two and a Half Men, Friends, and The Golden Girls, amongst others, made up over 234 billion viewing minutes throughout just 2020. At a time when bandwidths are strapped to begin with, rewatching old shows and films guarantees a safe blend of dopamine and a long-lost solace. Are producers cashing in on something as delicate as nostalgia in the recent wave of reunions, tv show reboots, live-action remakes and spin-offs? Has the uncertainty of the past two years simply withered our ability to process new media?

Traditional broadcasters and streaming platforms will continue to manufacture nostalgia as long as it sells. In his essay on ‘Why TV Remakes Are Everywhere Right Now’, Josef Adalian quotes a senior executive working in program development: “you know there’s some base ratings you’ll be able to get” hinting at the business case for remakes. It’s better for the bottom line. The nostalgia assures a baseline audience, while the novelty evokes curiosity from others. But as critical viewers, is it too early to think about the state of artistic inquiry? To ask for entertainment that ‘pushes the envelope’? Or should we just sink back into our popcorn strewn couches and revel in the familiar?

Svetlana Boym, in her book The Future of Nostalgia, traces the historical origin of ‘Nostalgia’ back to medicine. In the 17th century, a Swiss doctor coined the term to define the affliction faced by Swiss soldiers when “longing for their native land became their single-minded obsession”. The word comes from the ancient Greek roots: νόστος/nostos, meaning “return home”, and άλγος/algos, “sorrow” or “suffering”. Moreover, Boym identifies restorative nostalgia as emphasising “nostos” and proposing “to rebuild the lost home”. This is not unlike TV shows restoring their characters and plot in a contemporary setting to rebuild that lost ‘home’.

For instance, And Just Like That, a 2021 revival of Sex and the City tries to fit the original premise squarely in a world that has evolved beyond it. The characters in the original were written to navigate sex and love in the Upper East Side during the turn of the 20th century. It still had its problems, like most shows at the time: skimming over issues of race and sexuality or addressing them in bad taste. In a review, Lucy Mangan describes the revival as “granting our three Musketeers a valuable learning experience”. This happens as the characters stumble upon a laundry list of social issues, as if to singularly fix the oversights in the original.

Similarly, Netflix’s revival of the Gilmore Girls, titled A Year in the Life is set over a decade after the original’s finale. The revival felt anachronistic to the original, with fans questioning “Why didn’t Rory grow at all as a person?” revealing the way in which this character still felt trapped in the original. I revelled in the original’s sincere depiction of female ambition. The revival ventured out to perhaps explore the infallibility of the protagonist, finally letting her make mistakes. Without the creators lending this character the same compassion, or respect for that matter, this attempt felt sterile. It’s easy to revive a show, but not so much to imbue it with what made it special for so many different people.

The reunion does away with the herculean task of restoration, instead choosing to simply evoke the original’s spirit. This is why as far as ‘fan-service’ is concerned, reunions never claim to be more. Nostalgia, according to Boym, can be “reflective” or dwelling in “algia, in longing and loss, the imperfect process of remembrance”. The Friends Reunion, last year, saw its cast and creators return. As a show or movie completes its run, viewers get to imagine the ending they like best. When reboots simply teleport that story into the present day, they risk sinking this imagined ending and the franchise with it. This makes the reunion a risk-averse bid at monetising the original.

The story of Friends still ends, untouched. In a way, this may be a healthier form of processing the cultural impact of the show. We are then allowed the luxury of reflecting on all its missed opportunities to pioneer diversity, allyship or just cutting out those lazy fat-jokes. In doing so, the show preserves, for instance, Jay-Z’s music video for his song Moonlight (recreating a Friends episode with an all-black cast) as a cultural critique. I, for one, am thankful that J.K Rowling’s attempts at rewriting Harry Potter on Twitter were the first and the last. The creators of Harry Potter: Return to Hogwarts chose to cash in on nostalgia instead of ‘fixing’ the original. It’s not always worth recreating that lost magic, only to diminish the comfort that the original still offers.

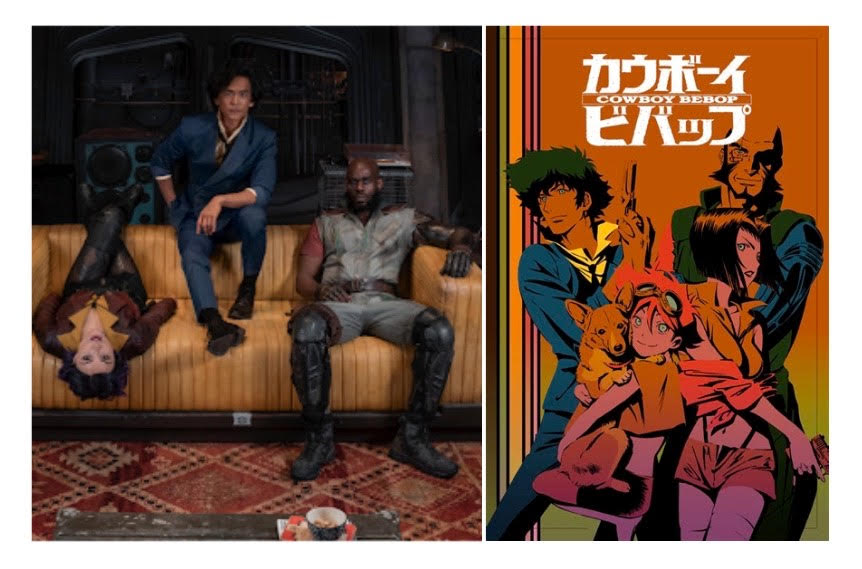

There seems to be no stopping the urge for restoration, though, so what works and what doesn’t? Late last year, Netflix released the live-action adaptation of Cowboy Bebop, the popular Japanese Anime known for its noir-style Sci-Fi story and existentialist, sardonic flare. A review expressed that the primary disappointment was the show’s “potential to excel” if the writing had preserved “the appeal of the original”. Remakes broadly suffer this fate when taking a beloved story (ahem, Lion King) to a different medium that doesn’t allow for the same freedoms. Most creative liberties, where many must be made in order to bring animation to life, will pale in unfair comparison to the original.

Gossip Girl was rebooted last year, with a new Gen-Z cast. Fans and bystanders alike noted how the reboot would never hold a candle to the original. Fortunately, it didn’t even try. Although the show loosely followed in the steps of the original, it evolved into its own story. It is still an escapist window into the inaccessible lives of wealthy teenagers roaming New York City, a large part of what made the original so popular. It also deals with social media, the current political climate in the US, and different social identities. If the show were to fail, it would fail on its own script while preserving the original Gossip Girl. No matter the ratings, this may at least be a more dignified take on the revival.

Is there a balance to be found between restorating old media and simply reflecting on the good old days? There is just a sliver of an opening in the writer’s room for enriching old stories with the stories we have today. By bringing in villains from Sam Raimi’s Spiderman and Mark Webb’s The Amazing Spiderman into the multiverse, Marvel’s No Way Home does the unimaginable. It actually incorporates them into the script without taking away from their original character arcs, while still writing its own story. Just this much is proof that it is indeed possible to judiciously use nostalgia as breadcrumbs, leading the viewers to unexpectedly witness a new story altogether.

A fan-made trailer for a Fresh Prince of Bel-Air reboot titled Bel-Air was released in 2019. It’s a darker, more dramatic take on the original sit-com, met with largely positive reactions. Will Smith is now producing the reboot. Smith is sourcing right from the fanbase, people who knew what made the original good and who know what they want to watch now. Gilmore Girls lost sight of what made the original such a comfort show, while And Just Like That knew what made it work in the first place, but failed to do its homework on what audiences want today.

Nostalgia-baiting is a sure-fire to assure an audience, for as long as the story is actually relevant. There will come a time when The Office or The Sopranos, as stories, will no longer resonate with future audiences. The success of manufacturing nostalgia isn’t guaranteed, but creators will continue taking a shot at restoration within the life-cycle of a show or movie. Time will tell whether Bel-Air strikes a balance between tying in parts of the original story and creating its own. It’s a precarious balance, but there is still room for new stories that older generations can be nostalgic about and that new generations can watch without wincing.

Devika Goswami is a student of Economics and Media Studies at Ashoka University. She can usually be found searching for another addition to her already overflowing to-be-read list.